WHO WAS WILLIAM HEATH DAVIS?

William Heath Davis, Jr. is one of the unsung, unknown heros of California history. For San Diegans he is a virtual stranger, yet it was he who used his $2304 in 1850 to purchase 160 acres of tidal and coastal land, stretching roughly from todays’s Pacific Highway on the west to Broadway on the north, Front Street on the east and Harbor Dive on the south. With four other business partners he created “New Town” San Diego, poised to compete with the existing Old Town. But New Town would have a modern pier (financed by Davis), with a military outpost to entice a federal presence to encourage city growth. Davis’s new city was created with fewer than a dozen wooden structures built from preassembled parts shipped from Portland, ME and sailed around Cape Horn. The idea of moving cargo from long distances was not a novel one for Davis. His home country of Hawaii had been modernized through goods shipped from America’s New England, a sixty-day shipping journey away.

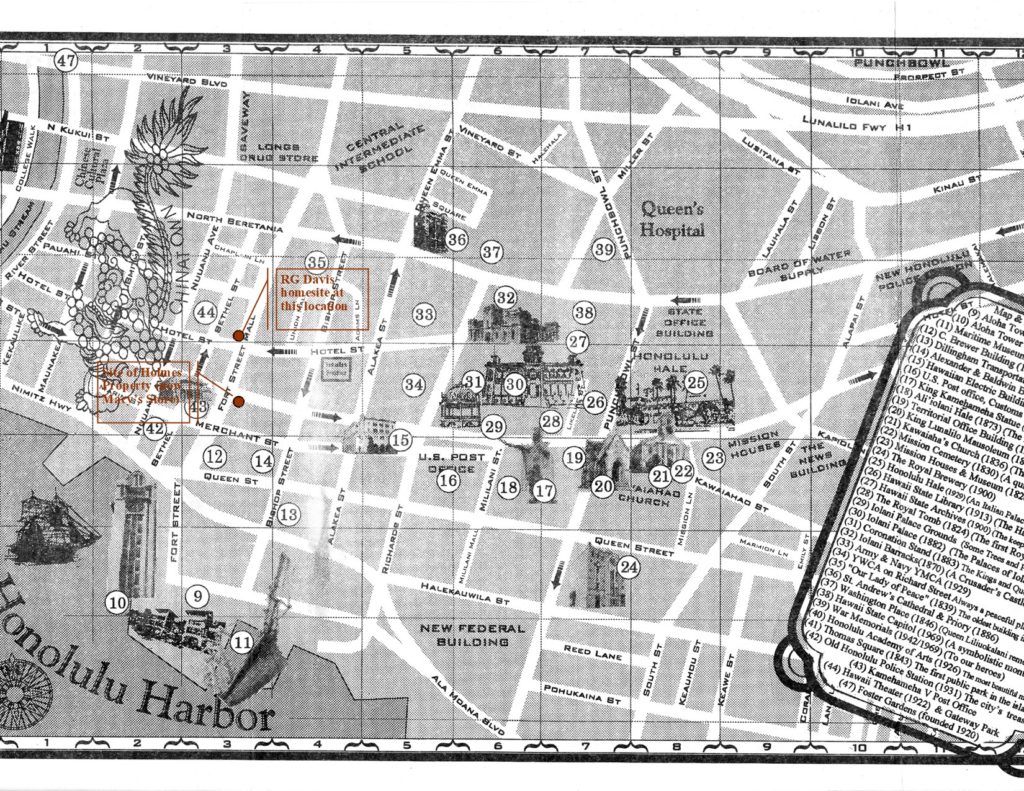

California’s historians know much about an adult William Heath Davis through his writings about California pre-statehood. Few have studied his early years or developed a sense of his Hawaiian surroundings from 1822-1838. This exhibit, “Wm. Heath Davis in Hawaii” attempts to explore those early years based upon historical writings, drawings, paintings and modern day “shoe leather” of attempting to walk the paths and streets where Davis walked in his early years in Oahu.

Come and meet Davis’ blue-blooded, if eclectic family with whom he grew up in Honolulu, early referred to as “Fair Haven” in the Sandwich Islands, now known as Hawaii. Perhaps you will have a sense of the early founder of downtown San Diego, one of the first council members of San Francisco…the man who took John Sutter down the Columbia River in search of gold in California…the man who selected San Francisco over Monterey to be the northern port of California.