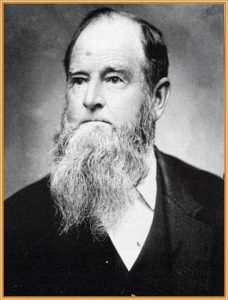

Alonzo Erastus Horton (October 24, 1813 – January 7, 1909) was an American real estate developer in the nineteenth century. Known as “The Father of San Diego,” the Horton Plaza mall in downtown San Diego is named for him.

Alonzo Erastus Horton (October 24, 1813 – January 7, 1909) was an American real estate developer in the nineteenth century. Known as “The Father of San Diego,” the Horton Plaza mall in downtown San Diego is named for him.

Horton was born 1813 in Union, Connecticut, the scion of an old New England family, and grew up in Onondaga County, New York. By his 20s he had developed a keen entrepreneurial spirit, and in 1834, at age 21, he began transporting grain by boat from the Lake Ontario port of Oswego, New York, to Canada. He also taught school there, and in 1834 ran for constable on the Whig ticket. But having developed a cough, and with his family and friends fearing tuberculosis, he was advised to move to the West. At that time, the Western frontier was Wisconsin, and in 1836 he moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. There he became a success at trading land and cattle.

In 1847, he purchased 1,500 acres of land in the rural wilderness of northern Wisconsin. In 1848 he filed the first warrant for what would become the village of Hortonville, Wisconsin, in Outagamie County near Green Bay, Wisconsin. At the time, the small settlement was quite far from the rest of the world. Today, although it is rather in the shadow of the larger cities of Green Bay and Appleton, Hortonville still exists as a village, with a 2009 population of over 2,700.

In 1851, with his town a success, Horton decided to join others in seeking his fortune in the gold fields of California. He sold his interests for $7,000, and traveled to El Dorado County, California, the heart of the Mother Lode. He became a success yet again, not so much through gold, but through trading ice and supplies in the mining towns. In 1857, he returned to Wisconsin. During an Indian attack, he lost a bag of gold dust worth $10,000, but kept the money he had made trading ice.

During the late 1850s and early 1860s, Horton spent some time in the East, even marrying his second wife, a prominent New Jersey woman. Horton’s first wife, whom he met in Wisconsin, had died of consumption. Horton is known to have married at least thrice, but relatives claimed he married about five times.

In 1862 Horton returned to California, this time to San Francisco, where he opened a furniture and household goods store at 6th and Market streets. While there, he heard about a growing settlement and interest in a small town called San Diego, located in far southern California, just north of the U.S.-Mexico border. It had become heavily acclaimed for its dry, warm, healthy climate, very welcome to many cold-weary Easterners. Upon visiting there, he noticed that while the small town was built around the old Spanish presidio (fortress) well inland near the mouth of the San Diego River, no large settlements had been made along the large San Diego Bay just a few miles south, even though all ships sailing to the town docked in the bay.

New Town San Diego

In 1867 Horton sold off his merchandise in San Francisco and journeyed to San Diego. There he bought 960 acres of land on San Diego Bay for just 27½ cents an acre. The district became known as “Horton’s Addition” or “New Town.” At first there was much opposition from the residents of the former site of the town center, which became known as “Old Town.” But new businesses began to flood into the new tract due to its greater convenience for ships arriving from the East. Eventually the new addition began to eclipse Old Town in importance as the heart of the growing city. Local land exploded in price throughout the 1880s, making Horton a financial success yet again. Horton helped to establish San Diego’s Chamber of Commerce in an effort to further expand the developing city. In 1867, Horton was the first person to ask for a public city park to be developed, which later became Balboa Park. More people from the East came in when the California Southern Railroad (now a part of BNSF Railway) became the first line to connect the city with the rest of America’s rail network in 1885. Unfortunately, land values crashed in the late 1880s, devastating much of Horton’s fortune. By the time he died in 1909, he had lost much of his former wealth.

Personal life

Horton went down in history as a tireless, enthusiastic supporter of the interests of whatever locality he happened to be living in, saying after moving to Wisconsin, “My principle is to be as happy as I can every day, to try and make everyone else as happy as I can, and to try to make no one unhappy.” He also had something of an effect on San Diego’s political scene. When he moved there in late 1860s, most locals, many of whom had migrated from the South or the border states, had supported the South during the Civil War and were Copperheads, or Democratic sympathizers of the Confederacy in an officially Union state. Upon being told that San Diego was a “Copperhead hole”, Horton remarked, “Then I shall make it a Republican hole,” and encouraged strong Republican sentiment in the city’s newspapers. A great supporter of Abraham Lincoln, he even grew his beard to resemble “Honest Abe’s.”

Horton was one of San Diego’s first Unitarians. He helped found the first Unitarian church in San Diego.

Horton died at age 96 in Agnew Sanitarium, San Diego. He is buried at Mount Hope Cemetery.

“Meet the Horton’s”

Join Alonzo Horton and two of his wives, Sarah Babe Horton and Lydia Knapp Horton, to hear about their days in early San Diego.

This video was created as part of our “Alonzo Horton: The Sesquicentennial of the Founding of New Town San Diego” exhibit.