Landmarks

Fresh Produce Year ‘round!

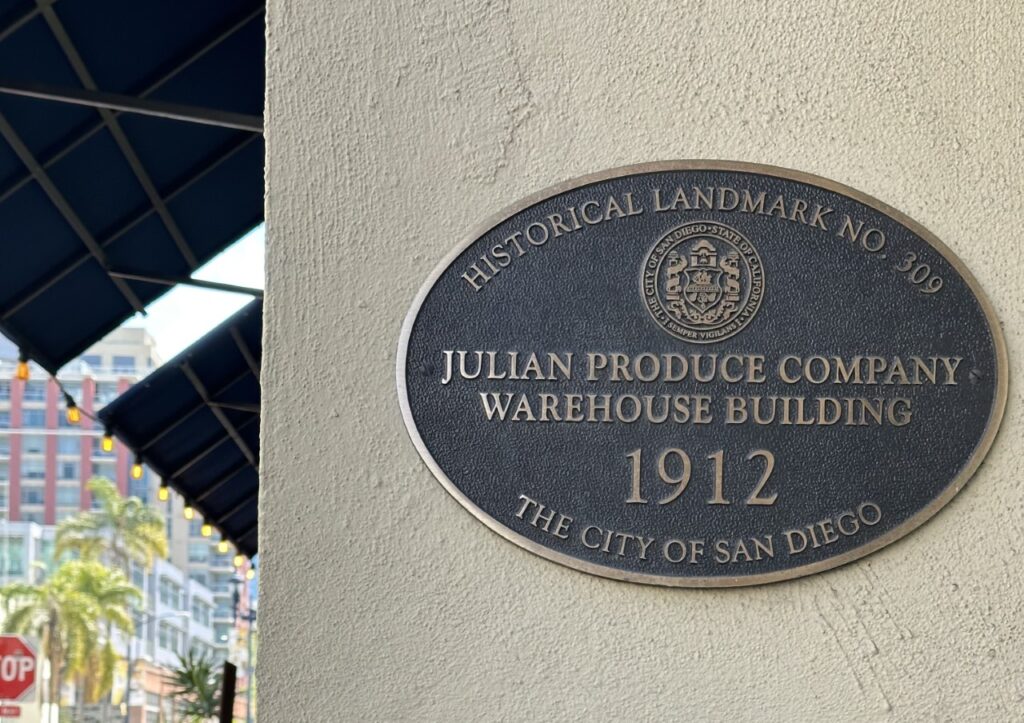

Julian Produce Company Warehouse

(1912)

679 J Street

Contractors: A & H Brownlee

Architectural Style: Italianate Revival /Commercial

In the 1880s, San Diego experienced an exceptional land boom, which caused the population to expand from 5,000 to 40,000 in only a few years. However, a world-wide recession followed, and by 1890 the population numbered 16,000 remaining residents. The town survived the fall of the real estate boom with the next decades providing for the growth of this port city and a renewed interest in agricultural production that would spur the city’s economic growth. Beginning in 1868, with the construction of Alonzo Horton’s 500-foot pier at the end of 5th Street, the community was served by an industrial and warehouse waterfront, which acted as a robust economic engine for the city until the mid-1950s. The area provided a major connection between the international incoming ships and the local commerce and related industries. Early exports included fruits, grains and other cultivated crops, as well as honey. San Diego became the number one producer of honey in the entire country!

In the early 20th century, San Diego’s civic leaders hoped for and promoted local agricultural production as a means of spurring increasing and sustainable economic growth. On July 19, 1911, in the official opening statement for the Panama-California Exposition, D.C. Collier extolled the virtues of San Diego as an “agricultural utopia,” hoping to lure visitors to come and remain in greater San Diego as farmers. His and others’ speeches proved effective, as a city of 16,000 hosted 3.7 million visitors, and additionally started a national craze for local Spanish Colonial Revival architecture that swept the country!

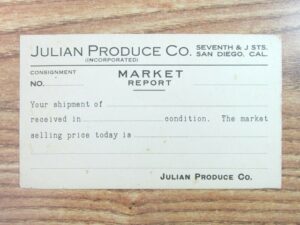

These expectations were definitely not denied, as the San Diego harbor became a very busy place. Even before the completion of the Panama Canal and the opening of the San Diego and Arizona railroad, the Julian Produce Company, billed as the largest

“commission Fruit and Produce House on the Coast” was boasting that it had “expedient facilities for handling and crating shipments on account of having railroad trackage facilities at the door and can load and unload cars at a minimum expense.” They additionally already had branches in San Francisco and Escondido, which “enabled them to have fruits during the entire season.” In the daily market reports, they solicited goods from local growers and promised to make prompt reports of remittance and would handle express shipments.

The business was started in 1899 by John E. Vince and C.K. Stout at 5th and I streets (now Island Ave.). As it expanded, the firm moved to larger quarters at 6th and I. Business was evidently booming as after only 6 months, the need for more space became necessary. Julian Produce had grown to include not only produce, but crawfish and watermelons from Mexico. Julian Produce Company entered into a contract with La Pescadora company to manage their entire output, and to expand shipment to Mexico City, Portland and Seattle. The weekly cargo was approximately 7000 pounds of succulent fish.

The watermelons, highly desired by San Diegans, were brought up from the extreme southern end of Lower California on the steamer, Benito Juarez. The first load of 1,050 melons was slightly delayed because of the loading of so many melons. For good measure, the load included cases of garlic, green peppers, cantaloupes, and eggplants. Not to waste space, the ship’s manifest also included 40 passengers!

By January of 1912, most of the company’s stock had been bought out by K.J. Horton – no relation to San Diego’s Alonzo Horton. This Horton was from Australia, but like our Horton, decided that San Diego was the best place on the globe. He had extensive experience in wholesale trade in both Australia and East Africa. He and his family set up residence on Front Street between Beech and Cedar.

In July 0f 1912, needing to expand, the company purchased a large block on the corner of 7th and J Streets for $25,000. The corridor between 6th and 7th was now known as “Produce Row.”

A chief investor, the Boone Investment Company, then commissioned building contractors, A. and H. Brownlee to erect an industrial structure. The two-story Italianate style building is of poured concrete with a flat roof. It represents a significant example of the early use of reinforced concrete in local building practices. The owners wanted a “strong, extra heavy” building to enable them to expand upward if necessary. The edifice featured large garage bays on 7th Avenue and framed in storefronts on J Street. The ground floor presented an asymmetrical facade with evenly spaced windows in horizontal rows. The second floor facade was symmetrical with evenly spaced windows. It featured paired, singe hung sash windows with boxed cornices supported by double brackets. Decorative flat pilasters alternated with horizontal spandrels adorned the front. Doors were single and provided entrance at various points. The use of decorative features represents the aesthetic and well as functional purposes of the structure.

The interior was considered very “modern” with large elevators, separate rooms for vegetables, fruits and other produce, separate rooms for nuts, grains, fish and even dairy. Eggs were 37¢ per dozen! There even existed a separate banana room to ensure that the fruit did not ripen too quickly. In 1917, Julian Produce decided to carry cacti, hoping to entice buyers to try the edible varieties. And – in 1919, Christmas decorations were also a staple, although they announced that the offerings for 1919 would be scarce due to the assemblage of California birds that stole the seeds and holly berries. Greens would be imported from Oregon. However, the price of potatoes was coming down, and stock prices for navel oranges were greatly increasing on the markets in New York and Philadelphia. Good news for the growers!

The Julian Produce Company building, like many of its former neighbors, now houses a popular eatery, The Blind Burro, on the street level. The restaurant features Mexican food made with fresh produce and ingredients, and with its logo, the burro, seeks to illustrate the culture of hard work and tenacity of Mexican agriculture. The second floor has offices and living spaces.

Sandee is the Historian and Lead Tour Guide for the Gaslamp Quarter Historical Foundation. She can be reached at [email protected].